Ulnar nerve entrapment occurs when the ulnar nerve in the arm becomes compressed (squeezed or restricted) or irritated.

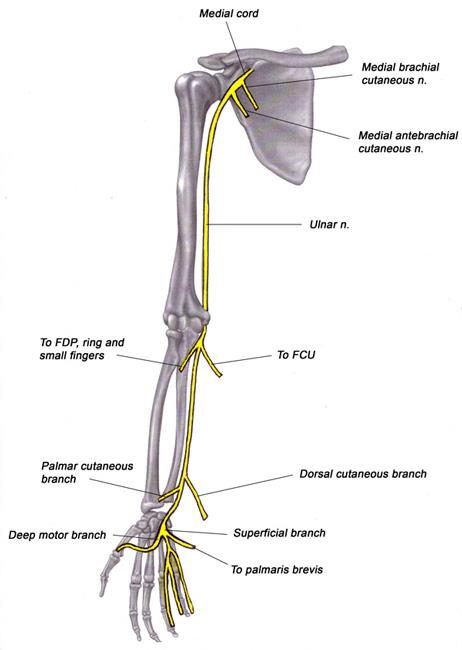

The ulnar nerve is one of the three main nerves in your arm. It travels from your neck down into your hand and can be constricted in several places along the way, such as beneath the collarbone or at the wrist. The most common place for compression of the nerve is behind the inside part of the elbow. Ulnar nerve compression at the elbow is called cubital tunnel syndrome.

Numbness and tingling in the pinky and ring fingers are common symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome.

Reproduced from Mundanthanam GJ, Anderson RB, Day C: Ulnar nerve palsy. Orthopaedic Knowledge Online 2009. Accessed August 2011.

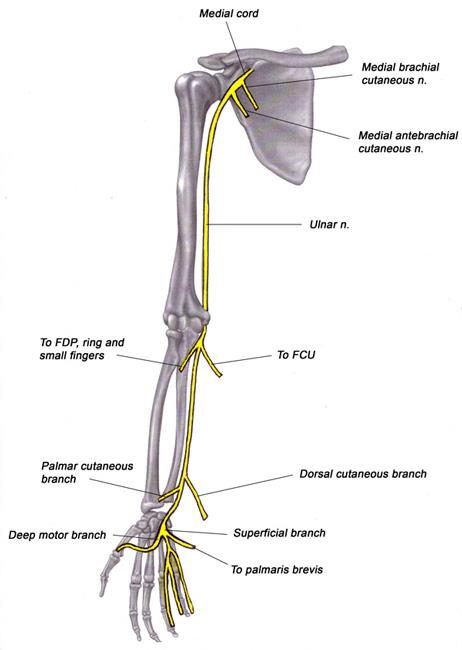

At the elbow, the ulnar nerve travels through a tunnel of tissue (the cubital tunnel) that runs under a bump of bone at the inside of your elbow. This bony bump is called the medial epicondyle. The spot where the nerve runs under the medial epicondyle is commonly referred to as the "funny bone." At the funny bone, the nerve is close to your skin, and bumping it causes a shock-like feeling.

The ulnar nerve runs behind the medial epicondyle on the inside of the elbow.

Beyond the elbow, the ulnar nerve travels under muscles on the inside of your forearm and into your hand on the side of the palm with the pinky finger. As the nerve enters the hand, it travels through another tunnel (Guyon's canal).

The ulnar nerve gives feeling to the little finger and half of the ring finger. It also controls most of the little muscles in the hand that help with fine movements, and some of the bigger muscles in the forearm that help you make a strong grip.

The ulnar nerve gives sensation (feeling) to the little finger and to half of the ring finger on both the palm and back side of the hand.

Cubital Tunnel Release

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

In many cases of cubital tunnel syndrome, the exact cause is not known.

The ulnar nerve is especially vulnerable to compression at the elbow because it must travel through a narrow space with very little soft tissue to protect it. Also, when you bend your elbow, you slightly compress and stretch the nerve and decrease its blood supply. This is often why the symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome get worse when the elbow is bent.

There are several things that can cause pressure on the nerve at the elbow:

Some factors put you more at risk for developing cubital tunnel syndrome. These include:

Cubital tunnel syndrome can cause an aching pain on the inside of the elbow. Most of the symptoms, however, occur in your hand.

(Left) Photo shows the appearance of normal muscle between the thumb and index finger when the fingers are pinched. (Right) In this photo, muscle wasting has occurred due to long-term ulnar nerve entrapment.

There are many things you can do at home to help relieve symptoms. If your symptoms interfere with normal activities or last more than a few weeks, be sure to schedule an appointment with your doctor.

Loosely wrapping a towel around your arm with tape can help you remember not to bend your elbow during the night.

Your doctor will discuss your medical history and general health. They may also ask about your work, your activities, and what medications you are taking.

After discussing your symptoms and medical history, your doctor will examine your elbow and hand to determine which nerve is compressed and where it is compressed. The doctor may also do a neck exam, as pinched nerves in the neck can cause similar symptoms.

Some of the physical examination tests your doctor may do include:

To perform Tinel's test for nerve damage, your doctor will lightly tap along the inside of the elbow joint, directly over the ulnar nerve.

X-rays. X-rays provide detailed pictures of bone. Most causes of compression of the ulnar nerve cannot be seen on an X-ray. However, your doctor may take X-rays of your elbow or wrist to look for bone spurs, arthritis, or other places that the bone may be compressing the nerve.

Nerve conduction studies. These tests can determine how well the nerve is working and help identify where it is being compressed. The test sends an electric current down the arm and looks to see if the current gets slowed along its path. If the current gets slowed down, this is likely an area of nerve compression. This can also help the doctor determine whether the pinched nerve is at the elbow, wrist, or neck.

Nerves are like electrical cables that travel through your body carrying messages between your brain and muscles. When a nerve is not working well, it takes longer for it to conduct.

Nerve conduction studies can also determine whether the compression is causing muscle damage. During the test, small needles are put into some of the muscles that the ulnar nerve controls. Muscle damage (especially with wasting) is a sign of more severe nerve compression.

Nerve conduction studies measure the signals travelling in the nerves of your arm and hand.

Unless your nerve compression has caused disability or any muscle wasting, your doctor will most likely recommend trying nonsurgical treatment first.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). If your symptoms have just started, your doctor may recommend an anti-inflammatory medicine, such as ibuprofen or naproxen, to help reduce swelling around the nerve.

Although steroids, such as cortisone, are very effective anti-inflammatory medicines, steroid injections are generally not used to treat cubital tunnel syndrome because there is a risk of damage to the nerve. However, sometimes your doctor will prescribe a short course of oral steroids (taken by mouth) to help relieve the inflammation around the nerve.

Bracing or splinting. Your doctor may prescribe a padded brace or splint to wear at night to keep your elbow in a straight position.

Nerve gliding exercises. Some doctors think that exercises to help the ulnar nerve slide through the cubital tunnel at the elbow and the Guyon's canal at the wrist can improve symptoms. These exercises may also help prevent stiffness in the arm and wrist.

Examples of nerve gliding exercises. With your arm in front of you and the elbow straight, curl your wrist and fingers toward your body, then extend them away from you, and then bend your elbow.

Your doctor may recommend surgery to take pressure off of the nerve if:

There are a few surgical procedures that will relieve pressure on the ulnar nerve at the elbow. Your orthopaedic surgeon will talk with you about the option that would be best for you.

These procedures are generally done on an outpatient basis (where you go home the same day as your surgery).

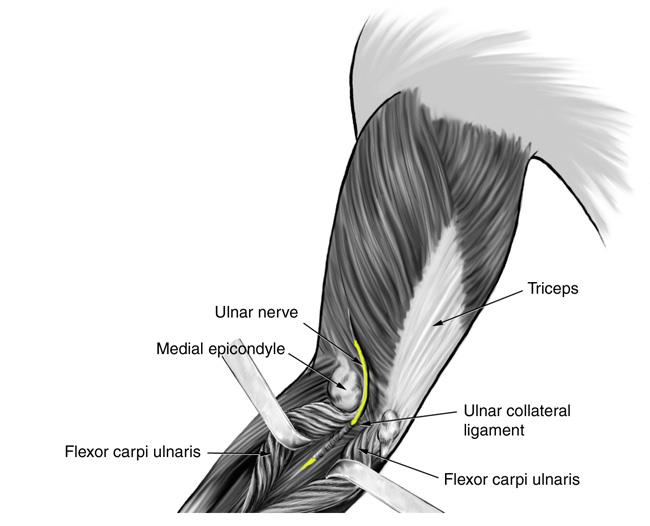

Cubital tunnel release. In this operation, the ligament roof of the cubital tunnel is cut and divided. This increases the size of the tunnel and decreases pressure on the nerve.

This illustration shows the path of the ulnar nerve through the cubital tunnel. Structures that may compress the nerve — such as the medial epicondyle and ulnar collateral ligament — are also shown.

Reproduced from J Bernstein, ed: Musculoskeletal Medicine. Rosemont, IL, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2003.

After the procedure, the ligament begins to heal, and new tissue grows across the division. The new growth heals the ligament and allows more space for the ulnar nerve to slide through.

Cubital tunnel release tends to work best when the nerve compression is mild or moderate and the nerve does not slide out from behind the bony ridge of the medial epicondyle when the elbow is bent.

In this surgical photo, a cubital tunnel release has been performed to decompress, or relieve pressure on, the ulnar nerve. The arrow shows the portion of the nerve that has become narrowed over time due to compression.

Ulnar nerve transposition. In most cases, the nerve is moved from its place behind the medial epicondyle to a new place in front of it. Moving the nerve to the front of the medial epicondyle keeps it from getting caught on the bony ridge and stretching when you bend your elbow. It allows a more direct path for the nerve and removes the compression on the nerve when you bend your elbow. This procedure is called a transposition of the ulnar nerve.

The results of surgery are generally good. Each method of surgery has a similar success rate for routine cases of nerve compression.

If the nerve is very badly compressed or if there is muscle wasting, the nerve may not be able to return to normal, and some symptoms may remain even after the surgery. Nerves recover slowly, and it may take a long time to know how well the nerve will do after surgery.